The Desmos Guide to Building Great (Digital) Math Activities

[2021 Feb 11: We’ve learned more about building great math activities. Check out this updated design guide!]

We wrote an activity building code for two reasons:

- People have asked us what Desmos pedagogy looks like. They’ve asked about our values.

- We spend a lot of our work time debating the merits and demerits of different activities and we needed some kind of guide for those conversations beyond our individual intuitions and prejudices.

NB. We work with digital media but we think these recommendations apply pretty well to print media also.

Incorporate a variety of verbs and nouns. An activity becomes tedious if students do the same kind of verb over and over again (calculating, let’s say) and that verb results in the same kind of noun over and over again (a multiple choice response, let’s say). So attend to the verbs you’re assigning to students. Is there a variety? Are they calculating, but also arguing, predicting, validating, comparing, etc? And attend to the kinds of nouns those verbs produce. Are students producing numbers, but also representing those numbers on a number line and writing sentences about those numbers?

- Match My Line is an activity for practicing graphing but we also ask students to sketch, settle a dispute, and analyze.

Ask for informal analysis before formal analysis. Computer math tends to emphasize the most formal, abstract, and precise mathematics possible. We know that kind of math is powerful, accurate, and efficient. It’s also the kind of math that computers are well-equipped to assess. But we need to access and promote a student’s informal understanding of mathematics also, both as a means to interest the student in more formal mathematics and to prepare her to learn that formal mathematics. So ask for estimations before calculations. Conjectures before proofs. Sketches before graphs. Verbal rules before algebraic rules. Home language before school language.

- In Lego Prices, we eventually ask students to do formal, precise work like calculating and graphing. But before that, we ask students to estimate an answer and to sketch a relationship.

Create an intellectual need for new mathematical skills. Ask yourself, “Why did a mathematician invent the skill I’m trying to help students learn? What problem were they trying to solve? How did this skill make their intellectual life easier?” Then ask yourself, “How can I help students experience that need?” We calculate because calculations offer more certainty than estimations. We use variables so we don’t have to run the same calculation over and over again. We prove because we want to settle some doubt. Before we offer the aspirin, we need to make sure students are experiencing a headache.

- In Picture Perfect, students can either calculate answers numerically across dozens of problems, or solve the problem once algebraically.

Create problematic activities. A problematic activity feels focused while a problem-free activity meanders. A problem-free activity picks at a piece of mathematics and asks lots of small questions about it, but the larger frame for those smaller questions isn’t apparent. A problem-free task gives students a parabola and then asks questions about its vertex, about its line of symmetry, about its intercepts, simply because it can ask those questions, not because it must. Don’t create an activity with lots of small pieces of analysis at the start that are only clarified by some larger problem later. Help us understand why we’re here. Give us the larger problem now.

- In Land the Plane, the very first screen asks students to “land the plane.” We try to keep that central problem consistent and clear throughout the activity.

Give students opportunities to be right and wrong in different, interesting ways. Ask students to sketch the graph of a linear equation, but also ask them to sketch the graph of any linear equation that has a positive slope and a negative y-intercept. Thirty correct answers to that second question will illuminate mathematical ideas that thirty correct answers to the first question will not. Likewise, the number of interesting ways a student can answer a question incorrectly signals the value of the question as formative assessment.

- In Graphing Stories, we ask students to sketch the relationship between a variable and time. Their sketches often reflect features of the context that other students missed, and vice versa.

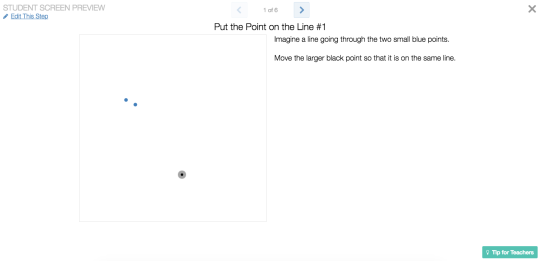

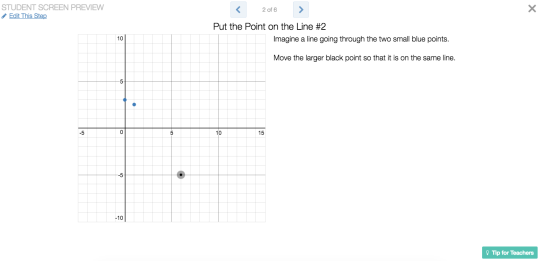

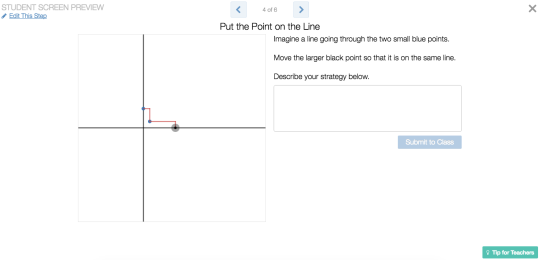

Delay feedback for reflection, especially during concept development activities. A student manipulates one part of the graph and another part changes. If we ask students to change the first part of the graph so the second reaches a particular target value or coordinate, it’s possible – even likely – the student will complete the task through guess-and-check, without thinking mathematically at all. Instead, delay that feedback briefly. Ask the student to reflect on where the first part of the graph should be so the second will hit the target. Then ask the student to check her prediction on a subsequent screen. That interference in the feedback loop may restore reflection and meta-cognition to the task.

- Our Marbleslides series offers students lots of opportunities for dynamic trial-and-error, for manipulating slopes and intercepts one tenth of a unit at a time until they collect all of the stars. But we also offer several static reflection questions where students can’t manipulate the graph before answering. We give them the chance to check their work only after they commit to an answer.

Connect representations. Understanding the connections between representations of a situation – tables, equations, graphs, and contexts – helps students understand the representations themselves. In a typical word problem, the student converts the context into a table, equation, or graph, and then translates between those three formats, leaving the context behind. (Thanks, context! Bye!) The digital medium allows us to re-connect the math to the context. You can see how changing your equation changes the parking lines. You can see how changing your graph changes the path of the Cannon Man. “And in any case joy in being a cause is well-nigh universal.”

- In addition to the examples above, Marcellus the Giant invites students to alter the graph of a proportional relationship. Then students see the effect of that altered graph on the giant the graph was describing. We connect the graph and the giant.

Create objects that promote mathematical conversations between teachers and students. Create perplexing situations that put teachers in a position to ask students questions like, “What if we changed this? What would happen?” Ask questions that will generate arguments and conversations that the teacher can help students settle. Maximize the ratio of conversation time per screen, particularly in concept development activities. All other things being equal, fewer screens and inputs are better than more. If one screen is extensible and interesting enough to support ten minutes of conversation, ring the gong.

- Our Card Sort activities feature only a handful of screens but offer students and teachers an abundance of opportunities to discuss both early and mature ideas about mathematics.

Create cognitive conflict. Ask students for a prediction – perhaps about the trajectory of a data set. If they feel confident about that prediction and it turns out to be wrong, that alerts their brain that it’s time to shrink the gap between their prediction and reality, which is “learning,” by another name. Likewise, aggregate student thinking on a graph. If students were convinced the answer is obvious and shared by all, the fact that there is widespread disagreement may provoke the same readiness.

- Charge! presents a relationship, a cell phone charging over time, that seems quite linear. As the cell phone completes its charge, the rate of charge slows down considerably, confounding student expectations and preparing them to learn.

Keep expository screens short, focused, and connected to existing student thinking. Students tend to ignore screens with paragraphs and paragraphs of expository text. Those screens may connect poorly, also, to what a student already knows, making them ineffective even if students pay attention. Instead, add that exposition to a teacher note. A good teacher has the skill a computer lacks to determine what subtle connections she can make between a student’s existing conceptions to the formal mathematics. Or, try to use computation layer to refer back to what students already think, incorporating and responding to those thoughts in the exposition. (eg. “On screen 6, you thought the blue line would have the greater slope. Actually, it’s the red line. Here’s how you can know for sure next time.”)

- In Game, Set, Flat, we ask students to create a bad tennis ball, one that doesn’t bounce right at all. Then we tailor our explanation of exponential models to their tennis ball, explaining how it violates assumptions of exponential models and how they can fix it.

Integrate strategy and practice. Rather than just asking students to solve a practice set, also ask those students to decide in advance which problem in the set will be hardest and why. Ask them to decide before solving the set which problem will produce the largest answer and how they know. Ask them to create a problem that will have a larger answer than any of the problems given. This technique raises the ceiling on our definition of “mastery” and it adds more dimensions to a task – practice – that often feels unidimensional.

- In Smallest Solution, we don’t ask students to solve a long list of linear equations. Instead we ask them to create an equation that has a solution that’s as close to zero as they can make it.

Create activities that are easy to start and difficult to finish. Bad activities are too difficult to start and too easy to finish. They ask students to operate at a level that’s too formal too soon and then they grant “mastery” status after the student has operated at that level after some small amount of repetition. Instead, start the activity by inviting students’ informal ideas and then make mastery hard to achieve. Give advanced students challenging tasks so teachers can help students who are struggling.

- In the conclusion of Water Line, after graphing the rising water line in several glasses we provide, we ask students to create their own glass. Then that glass goes into a shared classroom cupboard, giving students many more challenges to complete.

Ask proxy questions. Would I use this with my own students? Would I recommend this if someone asked if we had an activity for that mathematical concept? Would I check out the laptop cart and drag it across campus for this activity? Would I want to put my work from this activity on a refrigerator? Does this activity generate delight? How much better is this activity than the same activity on paper? 2016 May 11. Updated to add references to activities.